On A List of Movie Reviews

(For optimum viewing, adjust the zoom level of your browser to 125%.)

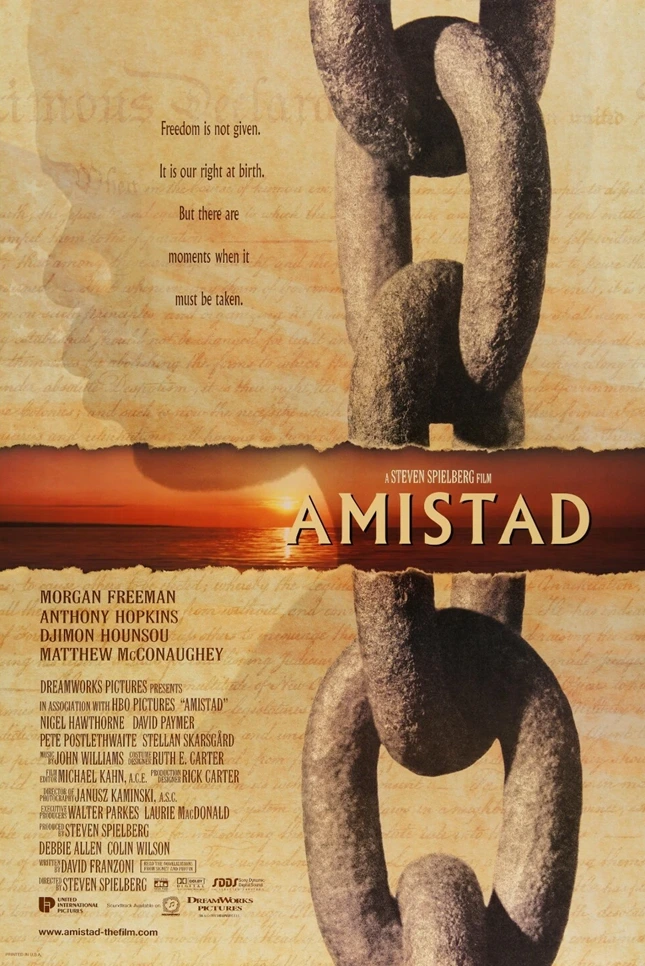

Amistad (1997)

Rate:

4

Viewed:

2/26

2/26:

Sure, Steven Spielberg gets credit for reintroducing the Amistad (Spanish for "friendship") case, which

had been completely forgotten after the Civil War, to the social consciousness, but the movie isn't

well-directed by any means.

As a matter of fact, it was never a cause of the Civil War between the North and the South but rather one of

the many incidents that were part of the slavery narrative that ultimately led to the Civil War. The Founding

Fathers didn't want to address it in the beginning prior to the construction of the U.S. Constitution because

doing so would've precluded that from happening; therefore, it became a matter of "when," not "if."

Earlier, I read Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and Its Impact on American

Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy by Howard Jones. What's shown in the film isn't accurate for the most part.

The following are the legal issues that had to be argued because they never happened before in United States

history:

1. Who owned the salvage rights? Those who first sighted La Amistad or Lieutenant Gedney and his men

who physically captured it?

2. Must the Africans be defined as part of the salvage rights, yet they, upon landing in New York and then

Connecticut, had been illegally branded as slaves? (Historically, the former was a free state while the latter

was a slave state; hence, the Africans were rerouted on purpose to embolden Lieutenant Gedney's claim,

so he could sell them as property.)

3. Had the owners of La Amistad retained the original rights because they were attacked by

the Africans prior to landing in the United States? If so, were they legally defined as slaves since they

weren't bound to the laws of the United States?

4. Did the Africans commit insurrection by murdering two men on La Amistad, or was it self-defense

because they had been kidnapped from their own country in Africa? If it's affirmative for the first question,

should they be tried in either Cuba or Spain? (The Spanish minister announced, "I do not, in fact, understand how

a foreign court of justice can be considered competent to take cognizance of an offence committed on board of

a Spanish vessel, by Spanish subjects, and against Spanish subjects, in the waters of a Spanish territory;

for it was committed on the coasts of this island, and under the flag of this nation.")

5. Therefore, why must this matter be decided in the United States? (The district attorney of

Connecticut, under orders of the federal government, actually represented Spain.)

6. Was the United States legally obliged to pay for the Africans' trip back to home if they're absolved of any

crime?

All are good questions, causing a lot of back and forth among courts which took two years to resolve, but

the movie has done an extremely poor job of answering or tackling any of them in depth. Steven Spielberg

should've watched Separate But Equal to understand how to handle a

court case of similar magnitude. The part where the defense team had to get a translator on the docks is true,

leading to the explanation of who the Africans were, where they came from, and how they got to this point.

What isn't mentioned in the film is that most people in Connecticut and elsewhere thought the blacks were

stupid, cold-blooded murderers who babbled constantly. The tide turned in their favor when they found out

the real story. Also, a cook told Joseph Cinqué (actually Sengbe Pieh) that he and the rest would

be killed and then eaten, and this frightened him to the point of instigating a mutiny.

Incidentally, Martin Van Buren (played by Nigel Hawthorne who's best remembered for his Oscar-nominated

performance in The Madness of King George) was pressured by

Spain to turn over La Amistad and its cargo to them under the Pinckney's Treaty of 1795, but that's not

the primary reason why he lost the re-election. It was the Panic of 1837, followed by a "five-year depression in

which banks failed and unemployment reached record highs," that cost him on top of being overwhelmed by a very

popular slogan his opponent William Henry Harrison ran: "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too." By the way, we're

exceedingly familiar with the word "OK" as in "okay," and it actually entered the lexicon for the first

time, thanks to Martin Van Buren who hailed from Kinderhook, New York, hence his nickname "Old Kinderhook."

Roger Sherman Brown (Matthew McConaughey in a highly redundant role after

A Time to Kill) wasn't an ambulance lawyer as portrayed in the film but

rather a distinguished abolitionist lawyer and would go on to be the governor of Connecticut. Even more shocking

is the minuscule treatment of Lewis Tappan (Stellan Skarsgård) who was among the most important figures of

the whole saga, having been responsible for, according to Wikipedia, securing legal assistance and acquittal

for the Africans, bolstering public support and fundraising efforts, writing daily accounts of the

proceedings for a New England abolitionist paper, arranging for several Yale University students to tutor

the imprisoned Africans in English, and organizing the return trip home to Africa for surviving members of

the group.

Forget Theodore Joadson (Morgan Freeman); he never existed in real life and is a constant embarrassment in

the film as nothing more than an observer. Djimon Hounsou is awful as Joseph Cinqué, turning into an

overblown romanticized figure. Anna Paquin as Queen Isabella? Oh, please...they should've gotten a girl who

could speak Spanish. On the other hand, I'm totally fine with Anthony Hopkins' performance as

John Quincy Adams, and he's the only performer to earn an Oscar nomination.

All in all, Steven Spielberg may have thought of himself as an indomitable historical storyteller after

Schindler's List, but he failed in Amistad and then again in

Munich and Lincoln.